Kapsula Magazine

February 2015

MUSEUM MISALIGNMENTS

Every day we make countless attempts to memorialize our experiences. We snap photographs, collect objects from our travels, write journals, build shrines, and spend hours re-imagining past events. As a society, we hoard precious objects in museums, build altar pieces, share funerary rituals, and canonize stories in books and theater. Memorialization is a response to our daily confrontation with loss. As our experiences evaporate we seek to compensate through various forms of representation. Any attempt to depict history or illustrate our observations is a romanticized abstraction, disclosing a human longing to preserve.

In this paper I describe how representation is a product of our shared desire to memorialize experience. I will focus on the museum as an institution that uses three-dimensional staging as a primary representational format. In the following accounts of my own experience with particular exhibitions, I draw attention to the viewer’s physical relationship to each setting: how scale, size, and movement through space dictate experience and modify the content of the story being illustrated.

Museums have varying degrees of visual and conceptual accuracy, which is rooted in the impossibility to present a complete and accurate version of history (Shafernich 1993, 45). In some cases this inaccuracy is visual, resulting in a crude or even grotesque appearance. In other examples it is the story being told that seems grossly incorrect. I will describe three American museums that demonstrate the beauty in imprecision and in some cases, the deeply disturbing vulnerabilities of representation: the House on the Rock in rural Wisconsin, the Thorne Miniature Rooms at the Art Institute of Chicago, and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello in Virginia. In each example, I describe instances of unintentional slippage in order to explore how representational errors are reverberations of our ever-present longing to remember.

THE STREETS OF YESTERDAY

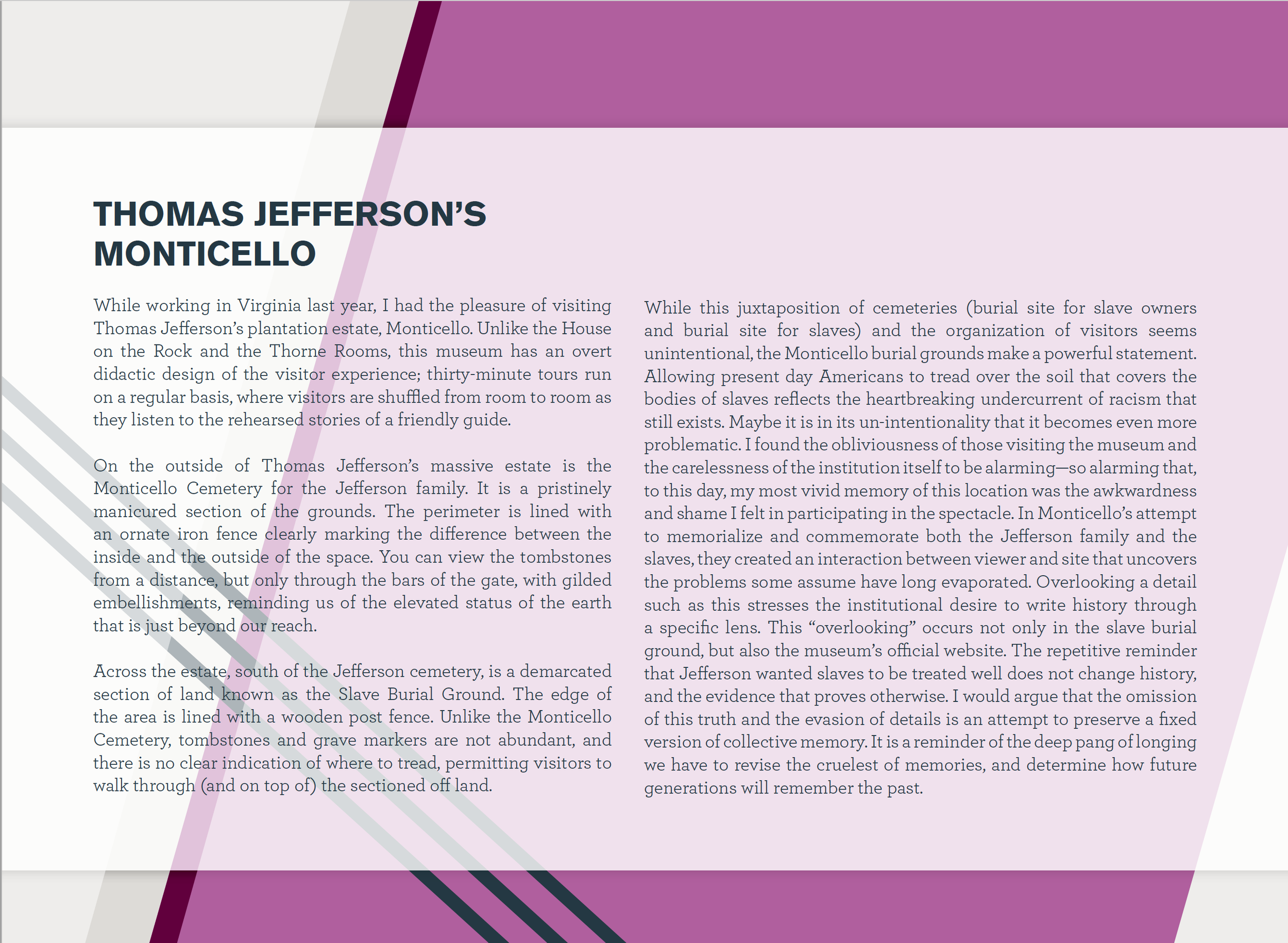

Three summers ago I took a road trip through Wisconsin using the Southwest Wisconsin Visitors Bureau multi-museum pass to get discounted entry at a number of tourist traps. The linchpin of southwest Wisconsin tourism is the House on the Rock, a quasi-museum created by the amateur architect Alex Jordan in 1940 (The House on the Rock, History 2015). It is more accurate to describe this site as a portrait of a passionate collector, rather than a museum with a didactic mission. In fact, Alex Jordan made it clear that he did not want the House on the Rock to be classified as a typical museum (Ibid).

The original house consists of 14 rooms, sitting atop a rock foundation in heavily wooded hills. Over time it has expanded with the addition of more buildings and elaborate garden arrangements. In the late 1980’s, shortly before his death, Alex Jordan sold the establishment to the collector, Art Donaldson who still owns the complex today (The House on the Rock, History 2015). The original house is saturated in eerie lighting with shag carpets and a lingering smell of mildew. (fig. A) It is filled with eccentric curiosities including: a collection of maritime memorabilia; The Infinity Room, a segment of the architecture that juts out from the house and creates the optical illusion that it continues infinitely (fig. B); Esmerelda, the robotic fortune-teller; and numerous token-operated music machines peppered throughout the museum. One of its exhibitions, The Streets of Yesterday, is a close-to-humanscale construction of an early 19th century outdoor street block installed inside of the building (The House on the Rock, Streets of Yesterday 2015). Walking through the street, I felt as if I had stumbled upon an abandoned town frozen in time.

The street is lined with storefronts housing objects that are grouped by category—a toy shop, the lamp store, and a clock maker to name a few. (fig. C) The windows are cluttered with objects, without the streamlined logic typical of American museums. One of the facades has a sign that reads “Apothecary.” Behind the window are dusty bottles claiming to cure all types of ailments and rusty objects that seem downright medieval—it seems impossible now to believe these tools were ever employed to aid human health. As if peering into an aquarium, you are faced with marvelous colors and forms pushed up against the glass. However, the space behind the objects is shallow, not at all like an actual shop; even the height of the storefront is oddly small. While the facade is punctured by its spatial limitations, the items within it are actual relics. Questioning the authenticity of the objects is not an immediate impulse, perhaps because we can immediately relate to their scale. Yet the subtle miniaturization of the stage is uncanny. Visiting the Streets of Yesterday feels different than a site museum construction where the museum visitors can make-believe they are walking through a town in some bygone era. The Streets of Yesterday transports the visitor to another place that is based on something real, yet asserts itself as non-history. This exhibit has all of the ingredients for nostalgia and utilizes visual cues that express to the viewer that it is a representation of the past, perhaps even a time and place we yearn for. Yet, the impossibility of the space has an “emerald city effect,” where the desire for an unattainable ideal is mistaken for the here and now.

THE THRONE MINIATURE ROOMS

The Thorne Miniature Rooms are miniature constructions of European and American interiors from as early as the 13th century. Similar to the Streets of Yesterday, they are representations that reflect the architectural and decorative styles of a time past. (fig. D) They were designed by Mrs. James Ward Thorne and are part of the permanent collection of the Art Institute of Chicago. They were meticulously built on a scale of 1 inch to 1 foot (The Art Institute of Chicago 2015). Each room is nestled in a cavity placed low on the walls.

My favorite room is called the French Provincial Bedroom of the Louis XV Period (Weingartner and Boyer 2004, 76). This bedroom is adorned with yellow floral wallpaper, upholstered chairs, and intricately carved furniture. The quality of light is the most mesmerizing characteristic of this room, which contributes to the construction’s elevated realism. The left wall has a large open window letting a stream of daylight pour into the space. The light makes shapes and shadows on the ground that seem so familiar, they would be easy to overlook. On the back wall, beside a yellow and red polka-dotted canopy bed, is a spiraling staircase that appears to lead to a second floor. The lighting on the stairs, although subtle, is warmer than the light coming through the window. A simple shift in color temperature differentiates the representational cues of natural and artificial lighting. While the meticulous carving on the bedroom’s armoire is exquisitely crafted, it is the quality of light that stimulates the most powerful sense of authenticity.

While visiting these constructions in person is irreplaceable, photography of the Thorne Rooms is compelling in its own right. In the Art Institute of Chicago’s exhibition book, Miniature Rooms, the camera is positioned slightly higher than standing height, which gives the viewer a subtle clue that we are peering into a miniature world. However, after flipping through my husband’s photographs of our visit in 2010, I noticed that he consistently positioned the camera to create the illusion that the viewer is actually standing in one of the doorways or lying on the floor. (fig. E) The edges of each container are eliminated from the frame. At first glance, some of the images appear to be of human-sized spaces. Then, as time passes, the reality of the room unhinges, and its believability dissolves—so why does this happen? These rooms are known for their intense representational accuracy in proportion and detail. The photographs are positioned and composed to create the feeling of just entering one of these rooms. While the prowess in the construction of these miniatures is beyond question, the evidence of abstraction is inevitable in even the most true-to-life examples. Perhaps, it is the accumulation of many infinitesimal errors that makes the truest of three-dimensional representations unachievable. Yet for me, it is that moment of realization when I become aware that I am looking not at a real-sized room, but a quite small one, that gives me the greatest satisfaction. Recognizing that I have been mistaken in this scenario is rather delightful. Inaccuracy in the miniature world produces the unmistakable quality of charm.

While the Thorne Rooms are magnetic, the utopian appearance of these spaces is unavoidable. The time of day, weather, and arrangement of furniture are far from imperfect. Because everything appears idyllic at first glance, it is the subtle strangeness and the minute implication of abstraction that make these spaces so hypnotizing, yet always out of reach. It is the uninhabitable nature of dollhouses that produces a persistent sense of yearning. Because the Thorne Rooms appear so life-like, we sink deeper into the illusion yet still remain aware of our position as onlookers, therefore heightening our sense of longing for the sweetness of a time that has long passed on.

THOMAS JEFFERSON’S MONTICELLO

While working in Virginia last year, I had the pleasure of visiting Thomas Jefferson’s plantation estate, Monticello. Unlike the House on the Rock and the Thorne Rooms, this museum has an overt didactic design of the visitor experience; thirty-minute tours run on a regular basis, where visitors are shuffled from room to room as they listen to the rehearsed stories of a friendly guide.

On the outside of Thomas Jefferson’s massive estate is the Monticello Cemetery for the Jefferson family. It is a pristinely manicured section of the grounds. The perimeter is lined with an ornate iron fence clearly marking the difference between the inside and the outside of the space. You can view the tombstones from a distance, but only through the bars of the gate, with gilded embellishments, reminding us of the elevated status of the earth that is just beyond our reach.

Across the estate, south of the Jefferson cemetery, is a demarcated section of land known as the Slave Burial Ground. The edge of the area is lined with a wooden post fence. Unlike the Monticello Cemetery, tombstones and grave markers are not abundant, and there is no clear indication of where to tread, permitting visitors to walk through (and on top of) the sectioned off land.

While this juxtaposition of cemeteries (burial site for slave owners and burial site for slaves) and the organization of visitors seems unintentional, the Monticello burial grounds make a powerful statement. Allowing present day Americans to tread over the soil that covers the bodies of slaves reflects the heartbreaking undercurrent of racism that still exists. Maybe it is in its un-intentionality that it becomes even more problematic. I found the obliviousness of those visiting the museum and the carelessness of the institution itself to be alarming—so alarming that, to this day, my most vivid memory of this location was the awkwardness and shame I felt in participating in the spectacle. In Monticello’s attempt to memorialize and commemorate both the Jefferson family and the slaves, they created an interaction between viewer and site that uncovers the problems some assume have long evaporated. Overlooking a detail such as this stresses the institutional desire to write history through a specific lens. This “overlooking” occurs not only in the slave burial ground, but also the museum’s official website. The repetitive reminder that Jefferson wanted slaves to be treated well does not change history, and the evidence that proves otherwise. I would argue that the omission of this truth and the evasion of details is an attempt to preserve a fixed version of collective memory. It is a reminder of the deep pang of longing we have to revise the cruelest of memories, and determine how future generations will remember the past.

CONCLUSION

Museums are sites of remembrance where we can meditate on our cultural and technological development. They are memorials for people, ideas, and events of the past. They house our collective desire to stop time and make sense of the world. Museums are incredible platforms for creatively representing the past, but they are also institutions with ideological commitments. The challenge with these institutions is what makes them so interesting: the fact that they are built by people. Like all other storytellers, museums can never present complete accounts of the past; they too have varying degrees of subjectivity (Shafernich 1993, 45). Therefore, we should interact with museums from up close and from afar, to grasp as fully as possible the histories we desire to understand.

The House on the Rock, The Thorne Miniature Rooms, and Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello are vastly different collections of knowledge. They each have a different purpose and distinct stories of development. However, they all have instances of visible slippage, where the inability to capture “reality” or accurately present history forms a different trajectory than what may have been intended in the first place. These misalignments, regardless of how charming or graceless, are reflections of our human desire to create stand-ins for the irretrievable histories we long to preserve.

WORKS CITED

The Art Institute of Chicago. “Thorne Miniatures Rooms.” Accessed

January 20, 2015. http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/thorne

The House on the Rock. “Section 2- Streets of Yesterday.” Accessed

January 20, 2015. http://www.thehouseontherock.com/HOTR_

Attraction_TicsAndTours_Reg_Tour2_Streets.htm

The House on the Rock. “History.” Accessed January 20, 2015. http://

www.thehouseontherock.com/HOTR_Attraction_History.htm

Shafernich, Sandra M. “On-Site Museums, Open-Air Museums,

Museum Villages and Living History Museums.” Museum

Management and Curatorship 12 (1993): 43-61.

Weingartner, Faninia, and Bruch Hatton Boyer. Miniature Rooms:

The Throne Rooms of the Art Institute of Chicago. New Haven and

London: Yale University Press, 2004.